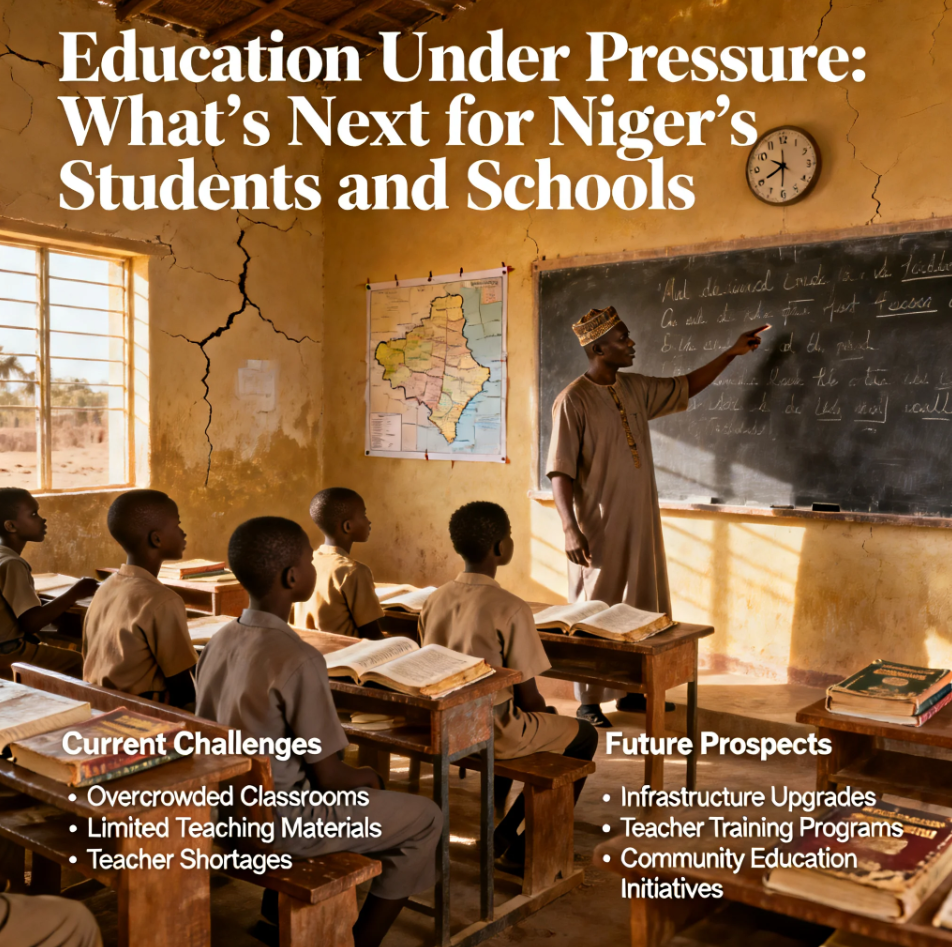

Niger’s education system is under intense strain from a combination of insecurity, displaced families, limited resources, and structural challenges. As schools close and children miss out on years of learning, questions loom large: What comes next for students and schools? This article examines the evolving crisis, its impacts on Niger’s children, and the strategies hopeful for the future of education in this fast-growing nation.

A System Already Struggling Before the Crisis

Even before recent upheavals, Niger faced longstanding challenges in education:

- More than half of children aged 7–16 were out of school, with some regions much worse off.

- Enrolment rates are low and retention declines sharply by secondary school, especially for girls.

- Poor infrastructure — including temporary “straw hut” classrooms — impacts learning quality and safety.

These structural problems created a fragile foundation that recent pressures have worsened.

Security and Displacement: Added Pressure on Schools

Insecurity across parts of Niger’s west and south has forced hundreds of schools to close in recent years, leaving tens of thousands of students without classroom access.

Displacement from conflict and threats pushes families to keep children home, disrupts peer networks, and makes schooling unsafe or inaccessible.

Learning Loss and Dropout Risks

Where schools remain open, students often struggle to keep up due to infrequent lessons, insufficient teaching materials, and the absence of catch-up programs.

Prolonged breaks from school can increase the risk of permanent dropout, child labour, early marriage, and recruitment into armed groups — all of which reduce lifetime learning and potential.

Investments and Plans for the Future

Despite the challenges, there are signs of strategic action:

- The World Bank has committed substantial financing to improve education quality, build more permanent schools, and expand girls’ access to education.

- Initiatives like Teach For Niger aim to strengthen teacher quality and increase community engagement in learning.

- Partnerships with UNICEF, UNESCO, and other agencies focus on child-centred pedagogy, data-driven planning, and addressing inequities in access and quality.

These efforts provide frameworks for resilience and reform even if progress will take years.

What Students and Families Want Next

For Niger’s children and parents, priorities include:

- Safe and secure schools that protect students from violence and disruption.

- Qualified teachers and classroom materials that support meaningful learning.

- Equity in access, especially for girls and children in rural or displaced communities.

- Opportunities for skills and secondary education that link schooling to future livelihood.

Realizing these goals depends on sustained government leadership, international support, and community participation.

Conclusion: Challenges and Hope

Niger’s education system is under pressure like never before — from insecurity, demographic growth, inadequate infrastructure, and social barriers. But with targeted investment, innovative partnerships, and a focus on equity and stability, there are ways forward. The journey will be long, but every child who stays in school brings the country closer to a more educated and resilient future.